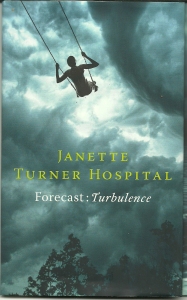

Compelling — Janet Turner Hospital’s Forecast: Turbulence

This is the first of a series of irregular posts (whenever I have time or the impulse to do them) about short story collections or individual short stories.

I have never been really convinced by Frank O’Connor’s claim in The Lonely Voice that the short story typically deals with a ‘submerged population group’, with ‘outlawed figures wandering about the fringes of society’. As a theory it seemed too neat—bound to apply to one story and not another. But reading Janette Turner Hospital’s superb collection of stories, Forecast: Turbulence, I was reminded again of O’Connor’s claim. All of Turner Hospital’s characters seem to be outsiders. There’s ten year old Lachlan from ‘Blind Date’ who although a ring-bearer at his sister’s wedding, can’t be trusted to walk in the procession because he’s blind—a blindness that Turner Hospital skillfully evokes without explicitly naming. There’s ‘weird Rufus’ who captains a whale-watching boat and talks to whales. There’s a lonely computer nerd in one story and abused teenage girls in another. A high school theatre director, Duncan, who is arrested for sexually harassing his students in ‘The Prince of Darkness is a Gentleman’ sentences his daughters to years of being outsiders as they try to escape his notoriety. In ‘Hurricane Season’ a grandmother and grandson are literally marooned by an approaching hurricane. The characters in this book are certainly individuals living on the fringes, apart from a well-functioning and caring community.

The short story cycle, like the short story, is undergoing something of a resurgence. Internationally, Elizabeth Strout’s magnificent Olive Kitteridge (2009) and Jennifer Egan’s cutting-edge, A Visit from the Goon Squad (2011) both took out the Pulitzer Prize for fiction ahead of novels. Forecast: Turbulence was shortlisted for the Prime Minister’s and The Age awards for fiction and won Queensland’s Steele Rudd Award. Unlike Strout and Egan’s books which derive their unity from one or two central, recurring characters, or Gillian Mears’s collection Fineflour, which uses the setting of the river flowing through a country town as a unifying element, this book is structured around the repeated metaphor of turbulent weather. It works. When the police knock on the door to arrest Duncan, a tornado, both literal and metaphorical is unleashed into the lives of his family. But the less literal examples are more impressive, such as the girl into self-harm who cuts ‘weather maps on my legs.’ (103) The central metaphor is an interesting feature of many fine contemporary stories and Turner Hospital takes it one step further by using it as a unifying motif for this collection.

Janette Turner Hospital grew up in Brisbane and has lived for many years in South Carolina. This experience of two places and cultures is surely an asset for a writer. Turner Hospital makes use of it by setting the first three stories in Australia and following them with six set in North America, ranging from Canada to the Carolinas. Usually the language and idiom fit the story’s locale. ‘Dumpsters’ for example, is a very American word that belongs in an American story. But occasionally Turner Hospital slips up. When Lachlan’s father, Jim, returns to Melbourne from the Burdekin in Queensland in time for his daughter’s wedding, he scoops up his son and ‘the ring cushion rises like a snowbird in flight and hovers over Pamela and falls.’(19) In what is a masterful ending, the simile jarred for me. The story is colloquially Australian—the daughter says, ‘I should tell you to bugger off, Dad’—yet a snowbird is North American. Although the additional connotation of someone who moves south to avoid winter and taxes seems to apply to Jim, the image of the snowbird can only be the author’s. It is wrong, to my ear, at least. It’s not that Turner Hospital is not careful with words, for her stories display a mastery of free indirect style, of the narrator’s voice taking on the idiom of her characters. The other instance that jarred for me was the young, self-cutting Tiyah, fishing at a secluded creek and saying, ‘It’s private weather down here.’(118) Turner Hospital has already established the special meaning of ‘private’ in this story, but it’s ‘weather’ that doesn’t fit, that I can’t really hear this character saying, that belongs to the author’s central motif rather than a character’s speech. These are clearly quibbles. It’s a testament to Turner Hospital’s art that they’re rare occurrences.

The protagonist of ‘That Obscure Object of Desire’, Nelson, is another lonely outsider, a software designer who is infatuated with a lady in a green nightgown he watches every night from behind a tree in a park. The woman reminds him of Daniel Gabriel Rossetti’s famous painting, Beata Beatrix. Like the Beatrice of Dante’s poem, this Beatrice is also idolised, with Nelson making her not only the woman of his dreams, but the hub of a labyrinthine on-line game that he creates and that becomes a popular craze. But after an incident at an office party, Nelson withdraws further and further into a world of dreams and illusion with horrifying consequences. It’s an affecting story of unrequited love, of a loner struggling to function in the real world. But as the story proceeds to Beatrice’s death, Turner Hospital provides a twist in the tale that I didn’t believe in. The ‘twist in the tale’ ending, which O. Henry made famous, is an ending that tends to foreground the cleverness of the author. When it works the shock of the twist feels organic to the story. When it doesn’t work the reader feels manipulated by an author pulling strings. Here, the ending felt like a leap too far to me, a turbulence that comes from nowhere. In contrast, the title story, ‘Forecast: Turbulence’ details the return of a father from the Afghanistan war after a five year absence with a twist that is completely shocking and completely right.

Overall, this is a dark collection. The final story, ‘Afterlife of a Stolen Child’ is a moving portrait of Melanie and Simon, whose two year-old son, Joshua, is stolen from outside a bakery. Turner Hospital employs two first person narrators, one who gradually seems to be Joshua’s murderer, one who years later identifies as the adult, stolen Joshua. It’s a complex and thoroughly modern story, where the reader is forced to question the reliability of the narration and to wonder whose version of events can be trusted. It’s also a harrowing portrait of the long term effects of guilt and grief and demonstrates how the short story, despite its length, can still accommodate a multiplicity of viewpoints. This is the story that should have ended the collection.

Instead, the book ends with a memoir, ‘Moon River’, that focuses on the author’s colonial ancestors and the death of her mother. Apart from a brief reference to an Aborigine who is shot, the tone is also colonial, as Oxley, we are told, ‘opened up the Liverpool Plains’. (227) It might well be the sort of the historical narration that Turner Hospital grew up with, but her memoir adopts rather uncritically the language and world-view of the colonisers. It’s beautifully written, but dramatically dull and is a rather anti-climatic ending to a strong book. ‘Moon River’ was previously published in a collection of Brisbane stories and that is where it should have stayed. It is not like Michael Ondaatje’s Running in the Family, where the entire book plays with generic diversity, but a blip on an otherwise coherent weather map.

Forecast: Turbulence is a diverse and confronting book. It deserves the accolades it has already received. It is powerful and compelling, demonstrating the range of the contemporary short story. My favourite moment is in ‘Hurricane Season’, when the grandmother, Leah, produces a box of photographs to peruse by candlelight. Steven, her grandson, picks out a photograph of an old lover, who rather magically rings her at the height of the storm on a phone resembling a nautilus shell. The story rises into a kind of magical realism where the turbulence of the hurricane replays the chaos of passionate love. Turner Hospital understands love, whether it’s long gone but not forgotten, or the immediate everyday love of grandmother and grandson. It’s a story about choices, those made in the present and those made in the past, and how they linger in people’s lives. Just as good stories linger and stay with you, just as this book will.

Forecast: Turbulence by Janette Turner Hospital. Sydney: Fourth Estate, 2011, pp. 232, AUD$23.99 Hardback, ISBN: 9780732294441