The Lives of Common People—Tony Birch’s latest book

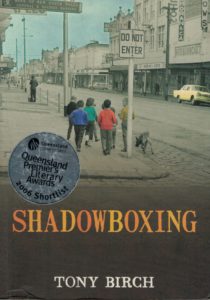

Tony Birch is giving the opening address at the upcoming Australian Short Story Festival in Adelaide on November 3-5, 2017. https://australianshortstoryfestival.com/ I’m looking forward to it. Earlier this year, I taught Birch’s first book of short stories, Shadowboxing to two classes of year 11 students at a high school in Casula. The book was popular with the students and I loved teaching it. This short story cycle dramatises the life of Michael Byrne as he grows up in Fitzroy in the 1960s.

My favourite story in Shadowboxing is “The Sea of Tranquillity”, which chronicles the car stealing exploits of Michael’s friend, Charlie Noonan. When Charlie eventually steals the maroon Mercedes that he’s lusted after, he crashes through a bluestone embankment into the Yarra river. The story then jumps a few months to the time of the Apollo 11 moon landing, with Michael limping about on crutches and Charlie dead. Michael is not interested in watching this historic moment, drawn more by the rear fin and tail-light of a 1964 Falcon surfacing in the flooded river. One of the things I like about Birch’s writing is the way he builds stories around central metaphors. In this story, the central metaphor is the moon, in other stories, it’s a red house, a father giving his son a boxing lesson, or a son cutting his father’s hair. Birch is not the only writer to use this device—I’m reminded of the electricity outages in Jhumpa Lahiri’s “A Temporary Matter”, a nightly cutting off of lights that provokes the young couple’s confessions to each other, or the uncollected birthday cake that results in the mysterious phone calls of Raymond Carver’s “A Small Good Thing”.

On the evening of the moon landing, Michael goes up to the roof of the flats where he lives and is joined by Charlie’s grieving sister, Alice. There’s something audacious about the way Birch writes this rooftop scene. It evokes the grieving of two adolescents and the awkward awakening of their attraction. Michael says, “Do you want to hold hands, Alice?” Alice moves away from him, but then sways back and slips a hand into his. This simple action of holding hands contrasts with the over-sexualisation of today’s youth culture, yet as a choice made by a writer it is honest, sexual and brave. Throughout the scene the moon hovers, vanishing from sight and then returning to end the story, becoming a metaphor for the yearning and desire that this story explores. It’s hard to explain exactly how and why Birch gets such metaphysical intensity from this portrayal of everyday life. It’s partly due to Charlie’s death, which hovers like the moon, unknowable in the lives of the characters, but it also owes much to Birch’s restraint. It’s as if he’s taken to heart Chekhov’s mantra that “in a story it is better to say not enough than to say too much”[i]. “The Sea of Tranquility” suggests and evokes much more than it actually says and this is the source of its power.

On the evening of the moon landing, Michael goes up to the roof of the flats where he lives and is joined by Charlie’s grieving sister, Alice. There’s something audacious about the way Birch writes this rooftop scene. It evokes the grieving of two adolescents and the awkward awakening of their attraction. Michael says, “Do you want to hold hands, Alice?” Alice moves away from him, but then sways back and slips a hand into his. This simple action of holding hands contrasts with the over-sexualisation of today’s youth culture, yet as a choice made by a writer it is honest, sexual and brave. Throughout the scene the moon hovers, vanishing from sight and then returning to end the story, becoming a metaphor for the yearning and desire that this story explores. It’s hard to explain exactly how and why Birch gets such metaphysical intensity from this portrayal of everyday life. It’s partly due to Charlie’s death, which hovers like the moon, unknowable in the lives of the characters, but it also owes much to Birch’s restraint. It’s as if he’s taken to heart Chekhov’s mantra that “in a story it is better to say not enough than to say too much”[i]. “The Sea of Tranquility” suggests and evokes much more than it actually says and this is the source of its power.

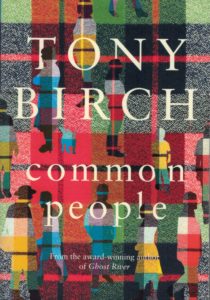

Tony Birch’s fourth book of short stories is the recently published collection, Common People. There are interesting connections to Shadowboxing such as in the story “Death Star”, where Patrick Cross is driving home a stolen car which hits black ice, wraps itself around a tree and bursts into flames. Here are two stories with similar premises, but I don’t think that Birch is repeating himself, more finding a new and different way to explore what feels like a similar artistic impulse. Patrick’s brother, Dominic, discovers his brother’s story and sets about revenging his death in a way that I found immensely satisfying.

Birch’s characters, as the title suggests, are ordinary people, and include the madam of a brothel, workers at an overnight pop-up abattoir, a retrenched journalist and a genealogist attempting to return a funeral home’s unclaimed ashes. Sometimes these characters have intriguing names such as “Harmless”, whose name reminded me of Fuckhead, the narrator of Denis Johnson’s short story collection Jesus’ Son. Another character is humorously called “Good Howard”, in opposition to the graffiti about our former prime minister, John Howard: “Howard lied—and sold out on refugees.”

There are a number of writers who have focused on people struggling to survive, the down and outs of society, the common people. At one stage in the development of Australian literature this genre was referred to as dirty realism. Much of it was unrelenting in its bleakness, its feeling of oppression and its lack of hope. Refreshingly, Birch avoids the pitfalls associated with characters who are trapped in their circumstances, with no way out. He doesn’t romanticise his characters or try to water down the difficulties they must deal with, but he manages to do what a lot of his predecessors failed to do—he offers a sense of hope.

There are a number of writers who have focused on people struggling to survive, the down and outs of society, the common people. At one stage in the development of Australian literature this genre was referred to as dirty realism. Much of it was unrelenting in its bleakness, its feeling of oppression and its lack of hope. Refreshingly, Birch avoids the pitfalls associated with characters who are trapped in their circumstances, with no way out. He doesn’t romanticise his characters or try to water down the difficulties they must deal with, but he manages to do what a lot of his predecessors failed to do—he offers a sense of hope.

“Harmless” is narrated by a thirteen year old tomboy, who doesn’t quite fit in with the other girls at school, who rides her bike around and becomes obsessed with the local homeless man known as Harmless. When another girl, Rita, unexpectedly goes into labour, the narrator takes her to an old timber cutter’s shack where she knows Harmless is living. The story is set in an unnamed country town with its typical prejudices and although it dramatises the experiences of two loners, what gives it a sense of hope is the way they help each other, the way their struggles result in a sense of community, even if it’s only a momentary one. The story “Joe Roberts” follows a similar trajectory, where a man who is sick and alone cares for a boy who has lost the key to his flat.

The beginning of “Colours” reminded me of Sherman Alexie’s story, “The Toughest Indian in the World”. Tony Birch’s story begins:

My grandfather taught me about the sky. At night he would take me out walking in the paddocks behind the government house we lived in on the Reserve. He’d tell me to look at the sky while he took a pouch of tobacco from his pocket and rolled a cigarette…. Only when he’d finished would Pop point one of his nicotine-stained fingers at the stars and tell me that a night would come sometime in the future when the stars would save me.

The narrator of Sherman Alexie’s story, a Spokane Indian, says:

When I was a boy, I leaned over the edge of one dam or another—perhaps Long Lake or Little Falls or the great gray dragon known as the Grand Coulee and watched the ghosts of salmon rise from the water to the sky and become constellations. Believe me, for most Indians stars are nothing more than white tombstones scattered across a dark graveyard.

“Colours” begins by evoking the relationship between grandfather and grandson and builds to a brutal and unjustified police arrest, where the grandson is actually saved by the prediction of his grandfather. The leap at the end of this story owes something to magical realism or perhaps to an Indigenous way of seeing the world that Birch shares with Alexie.

This book about common people is uncommon in its portrayal of hope and the emergence of community in unlikely situations, in the way kindness can triumph over adversity and shine down on us like stars, like secret stories waiting to be told. Common People is a book waiting to be read—get into it and discover its marvellous secrets now. Get to the Australian Short Story Festival in Adelaide this November to discover the rich and wonderful world of Australian short fiction.

Shadowboxing by Tony Birch. Scribe, Melbourne, 2006. 178pp. ISBN: 1920769706.

Common People by Tony Birch. UQP, ST Lucia, 2017. 218pp. ISBN: 9780702259838

[i] Chekov, Anton. “On the Problems of Technique in the Short Story.” What is the Short Story? Eds. Eugene Current-Garcia and Walton R. Patrick. Glenview, 1974, p21.