Andy Kissane launched Duck Soup and Swansongs by John Carey, (Ginninderra Press, 2018) at the NSW Writers’ Centre in Rozelle on March 11, 2018.

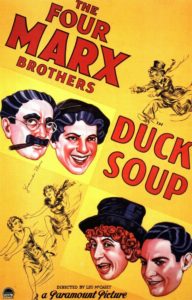

It’s a hard task to sum up a John Carey book, to pin it down. You can’t really do it—for the variousness of John’s poetic achievement resists summary, it resists labels. My predecessors have used lists in an attempt to capture the flair of John’s previous books. Michael Sharkey refers to the “splendid turns of phrase and startling images in this collection of meditations, graceful tributes, celebrations, narratives, life stories and acerbic satires” that made up John’s third book, The Old Humanists. joanne burns says of his fourth book, One Lip Smacking that it pulses with “a distinctive brio, a perky wit and a parodic playfulness”. Carey “offers the reader a perspective on Sam Spade’s socks, Poirot’s apprentice, a stand-up psychiatrist, the Goons, Facebook ‘friends’, an abduction by aliens, a Wikipediac revision of the demise of Julius Caesar and 3rd Age Villagers trained in karate, who ‘smash imaginary Ikea furniture to splinters’.” And that’s not all! One could construct a similar list to catalogue the incredible range of subjects that Carey responds to in Ducksongs and Swan Soup, such as a condensed Catholic boyhood, the unreal world of TV, a history of balloons, a Gonzo take on literature and film, what can happen in the soundproof chamber at the MCA, the credibility of a defence alibi where you claim you spent the night with the prime minister, the experience of a Japanese capsule hotel, dream homes, and an attack of killer icons.

I am sorry, I did mean to say, Duck Soup and Swansongs, to give the book its correct title. “Responds” is not quite right either, for John Carey doesn’t merely respond to a subject, he recreates and re-imagines it, until we’re seeing it with brand new eyes. He possesses an imagination and a focus that’s prepared to wander anywhere, to investigate anything, to satirise anyone who deserves it, from Tony Abbott’s idea of a captain’s pick to those spin doctors sending their clients for identity makeovers.

I am sorry, I did mean to say, Duck Soup and Swansongs, to give the book its correct title. “Responds” is not quite right either, for John Carey doesn’t merely respond to a subject, he recreates and re-imagines it, until we’re seeing it with brand new eyes. He possesses an imagination and a focus that’s prepared to wander anywhere, to investigate anything, to satirise anyone who deserves it, from Tony Abbott’s idea of a captain’s pick to those spin doctors sending their clients for identity makeovers.

John Carey is a funny man and a very funny poet. I doubt that this is news to anyone here. If it is, then you only need to turn to the first poem of this book, “Individual Agreement” which reads, as a letter to an employer:

Sir, about the clause in my contract

that says I will need to have a leg amputated

to enhance my visual and affective impact

for the street-corner phone-plan sales team

I have a question.

Do I get severance pay?

Here the poem builds to a punch-line at the end and imitates the structure of the bar-room joke. But this is only one form of Carey’s humour, which is as various as his subject matter. There’s the wonderful title of “Report from the Circuit Judge of the Mountain View Rhododendron and Arts Festival Poetry Competition” which reminds me some of the long titles of the American poet James Wright, such as, “Depressed by a Book of Bad Poetry, I Walk toward an Unused Pasture and Invite the Insects to Join Me.” I won’t read this poem, because I think John is going to, but I just want to quote two lines that remind me of Gilbert & Sullivan. The judge is running through his shortlist, which includes:

a concrete poem that made the line count problematical;

a PiO pastiche entirely in formulas mathematical;

John’s poetic voice is as varied as his subject matter—his poems are double-voiced and polyphonic in the way they draw from the lingo of the media and popular culture, from fashion and capitalism, and from Australian colloquialisms past and present. I have the sense that John instinctively knows how to be funny, that it comes naturally to him, at least that’s how it seems to me. Listen to the energy and movement at the start of “Comedy Writing 101”:

Save the modifiers for your doctoral thesis.

In this class they look like a failure of nerve.

Disguise and surprise are the essence. Be a wolf

in sheep’s clothing or Grandma’s bedjacket, then

reverse the terms. Play silly buggers with the punter’s

expectations, like the cartoon duck who surprisingly

side-steps the falling piano by stooping to pick up

a false nickel lure then waddles on straight into

an open manhole.

Groucho & Harpo Marx, eat your hearts out. John Carey is a poet who plays silly buggers with the punter’s expectations, and I am glad he does. The Duck Soup section of this book is full of poems with surprising lines, surprising takes on the world. For example, Carey puts Brett Whiteley and Arthur Rimbaud together in his WB Yeats prize winning poem, “Brett and Arthur”. This might not be surprising, for those that know that Brett was a fan of Rimbaud and painted a portrait of him. There’s an easy rhythmic discursiveness to Carey’s lines:

I have seldom found the surrealist mode disturbing

where the psyche seems to reach out to the ambient world.

There is often a lush efflorescence in the works

more fluid and dynamic than the clinging shapes,

the stalled moves and furred textures of nightmare. Here,

there’s a South Seas sunniness that undoes Arthur’s ferocity.

For the better, perhaps. And Whiteley’s other representation

of Arthur? The sculpture of two huge matches, one live, one dead?

I must have blinked and missed the flare in between. Or I needed

warmth in my life, not a conflagration. A lost weekend

in Hell was season enough and illumination best dammed

and released in a steady trickle of lucidity.

Carey has something interesting to say about these artists and their works, which builds to the very original description of Whiteley’s match sculpture as a second portrait of Rimbaud, moves to the  speaker’s reaction to this, and cleverly manages to work in both the title of Rimbaud’s book (A Season in Hell) and a pun on damnation and damns which then glides into the metaphor of trickling lucidity. This is skilful, intelligent art at the level of the line and the poem, that is much more difficult than it seems, and John Carey pulls it off in poem after poem. Writing comedy is difficult and important work, as Michael Sharkey wrote in the now defunct journal, Five Bells: “Laughter is the sign of communal bonding. Even when we laugh alone it is the sign of some conditioned identification as a result of our socialisation…”

speaker’s reaction to this, and cleverly manages to work in both the title of Rimbaud’s book (A Season in Hell) and a pun on damnation and damns which then glides into the metaphor of trickling lucidity. This is skilful, intelligent art at the level of the line and the poem, that is much more difficult than it seems, and John Carey pulls it off in poem after poem. Writing comedy is difficult and important work, as Michael Sharkey wrote in the now defunct journal, Five Bells: “Laughter is the sign of communal bonding. Even when we laugh alone it is the sign of some conditioned identification as a result of our socialisation…”

John Carey’s poetry is a richly communal poetry, it is full of glimpses of the absurdity of our social lives. And it contains a humour that surprises—a verb used by both Sharkey and Joanne Burns and by John himself in “Comedy Writing 101”. John Carey writes surprising poetry. Of course, I imagine that John would give little credence to the practise of the purple puff, he even satirises blurbs in the last poem of this book. Zelko Boz, a psychotherapist from Zagreb, writes:

‘There is an unearned quality about his originality,

as if he is always writing a pastiche

of some work of which he has the only copy.

You remember nothing from his scribblings

except the curious way he goes about them.’

I couldn’t disagree more. There’s an earned quality about John’s energetic, erudite poetry on every page of this book. And if the flip side of a comic vision is a serious vision, then John Carey has it in spades and always has. His seriousness can certainly be found in the poems that make up the Swansongs section, but it is also there in Duck Soup. There’s a focus on art that ranges from the war prints of Otto Dix to the contemporary sculptures of Anish Kapoor, and a number of poems that deal with music. Here’s the melodic and beautiful first stanza of “After Bird”:

A butcher-bird sings punctually at six a.m.

dancing ribbons of melody, each line of ten notes

with a shorter bridge of four or five, then a reprise

after an irregular number of pulse beats.

The song seems to link arms with a tune by a young

Ornette Coleman: little mariarchi licks, slurred runs

in the lower register, honks and sudden fractures

with blue notes and field cries tipping into the crevices.

There’s an examination of the injustice of the former copper mine in Bougainville, in a convincing and powerful political poem, and the imaginative leap into the world of a blind person in “Navigation”:

Is the street completely unfamiliar or newly so,

turned into a slalom course of jostle and shin-bark,

or a field of unknown depth that needs sounding?

For a sighted person, it is like trying to remember

a child’s unnameable world of unknowing.

You can shut your eyes in a parody of empathy

knowing you can open them on what was there before

and feel ashamed of taking for granted

a fragile, fallible thing, so easily tricked

by a magician’s patter and business.

I am no longer surprised by the empathy that throbs, pulses and shines from John Carey’s poems. At the level of the line he consistently thrills, but his project is ultimately a communal one—to write us into our world, into the experiences of others, so we see and understand them. The English novelist Graham Swift wrote of fiction:

“One of the fundamental aims of fiction is to enable us to enter, imaginatively, experiences other than our own. That is no small thing. The hardest task in the world, against which consciousness stacks insuperable obstacles, is to understand what it is like to be someone else, but upon that vital mental endeavour so many of our moral, social and political pretensions depend. Fiction, after all, serves the real world. No fancy theories are needed: it begins with strangeness, it takes us out of ourselves, but back to ourselves. It offers compassion.”

As for fiction, so also for the poetry of John Carey. He writes with compassion, a compassion that deserves to be treasured. It is natural that a relatively young man, as John is, should write some swansongs, but I for one, hope that this is not his last book. As John writes in “Horn” about Bernie McGann’s saxophone:

…. waiting like an old dog tied up

outside a pub for its master to shuffle out

and take it for a final lollop in the park

put it through its larrikin paces and old tricks.

Surely there’s more life in the old dog yet, more larrikin paces and old tricks. In the poem, “Australian Poetry 1850-1945”, Carey writes:

When gullies were dales and creeks were brooks

there were four-figure sales for poetry books.

Duck Soup and Swansongs deserves to get four figure sales. It’s a book that I can’t do justice to, except to say that it is bloody funny, surprising, moving and enriching. I am delighted and honoured to be sending it out into a world that needs its humour, its wisdom, its compassion and its art. My congratulations to Stephen Matthews of Ginninderra Press for publishing another fine book and to John Carey for writing it. I know that you will enjoy reading it.

John Carey’s book is available from Ginninderra Press: Duck Soup and Swansongs